Poland Faces a Pivotal Election. Observers Say It Isn’t a Fair Vote.

By Emily Rauhala, Kate Brady, and Loveday Morris | 13 October 2023

Poland will vote on Sunday to determine whether a political party accused of whittling away the country’s democracy can stay in power, but an election billed as the most important in a generation has been clouded by concerns it will be only partially free and far from fair.

Since it came to power in 2015, the right-wing populist Law and Justice party has drawn ire from European Union allies for politicizing the judiciary, turning the media into a party mouthpiece and eroding the rights of minorities. The leader of the opposition, Donald Tusk, a former Polish prime minister who also served as president of the European Council, has vowed to restore rule-of-law in Poland and make peace with Brussels.

After a campaign season full of heated rhetoric and bitter recriminations, polls showed a tight race, with analysts predicting that neither side would secure a clear majority, probably leading to a coalition government led by one of them.

The outcome will be closely watched across Europe, where diplomatic clashes with Poland have become an enduring source of division and angst, as well as in the United States, which has grown closer with Poland since Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

But officials and analysts say what Polish voters really want is being distorted by state-controlled media, new electoral rules and a controversial referendum that’s been tacked on to the vote.

The election has compounded fears about the health of Polish institutions. “We still have a democracy in Poland, but it’s thanks to our civil society, nongovernmental organizations and local government that the opposition is relatively strong,” said Warsaw mayor Rafał Trzaskowski, who is associated with Tusk’s center-right Civic Platform.

“We can argue that it’s still democratic,” he continued. “But, of course, it’s also completely unfair.”

After eight years consolidating its hold over the media, with Poland dropping from 18th to 57th out of 180 countries in the World Press Freedom Index, Law and Justice has been able to rely on disproportionately favorable campaign coverage, while using the public broadcaster and a network of regional newspapers to amplify its attacks on the opposition.

Broadcaster Telewizja Polska (TVP) — which is stacked with Law and Justice party loyalists and this year received 2.35 billion zlotys ($546 million) in government funds — devoted 80 percent of its political airtime to the ruling coalition, giving only 20 percent to opposition parties, according to the Polish National Broadcasting Council’s monitoring in the second quarter of this year.

TVP has routinely downplayed opposition rallies, including a big demonstration in Warsaw this month. While city officials estimated turnout at 1 million, TVP reported that 100,000 people attended.

And when the ruling party found itself accused of granting work visas for large sums of money — contradicting its hard line stance on migration, and leading to the resignation of the deputy foreign minister and the indictments of other officials — TVP went with the headline: “Opposition is deliberately lying on visa scandal: Polish FM.”

“There has been a constant flow of pro-government propaganda for months, for years, praising the achievements of the government and attacking the opposition in an unprecedented way,” said Piotr Buras, head of the European Council on Foreign Relations in Warsaw.

“The public media is an instrument of power,” Buras said. “It’s the same instrument that was used in the 2019 election, but now it’s used to the extremes.”

In the run-up to this vote, the No. 1 target has been Tusk, cast by Law and Justice leaders — and echoed by the public broadcaster — as the “personification of evil” and a treacherous turncoat who has put the interests of Russia and Germany over Poland’s.

One video clip that has been played on repeat shows Tusk saying “für Deutschland,” or “for Germany.” But the clip itself was a two-word cut taken from an innocuous message to Germany’s conservative CDU party in January 2021 and stripped of all context.

The government has also raised eyebrows by holding a referendum alongside Sunday’s parliamentary election. The ballot consists of four loaded questions that aren’t tied to any policy proposals but are instead designed to drum up support for Law and Justice while promoting misinformation about the opposition, Human Rights Watch and other European observers say.

For instance, one question asks whether people want to admit “thousands of illegal immigrants” from the Middle East and North Africa as “imposed” by the “European bureaucracy.” Another questions asks if voters want to dismantle a barrier erected on Poland’s border with Belarus.

Michal Baranowski, managing director of Warsaw-based GMF East, part of the German Marshall Fund, said the referendum is a way to get around campaign finance restrictions because it deploys state resources to spread nonneutral election information.

Using the apparatus of the state to back a referendum is “another vehicle for funds for campaigns” and “creates a disparity in the amount of funds used by one side not the other,” he said.

For the referendum to be valid, 50 percent of the electorate must participate. Opposition leaders have called for a boycott. A former head of Poland’s electoral commission, Wojciech Hermelinski, said he “would be ashamed to take part.”

But simply accepting a referendum ballot — which will be handed out with the ballot paper for the parliamentary election — is considered participating. Voters must actively refuse the referendum paper — which some observers worry will discourage people from participating in the parliamentary vote or compromise ballot secrecy.

“There are real concerns,” said Malgorzata Bonikowska, president of the Center for International Relations in Warsaw. “Especially among people who work in the public sector. But also those in business.”

New electoral rules, signed into law in March, have increased the number of polling stations and mandated free transportation on Election Day for elderly voters and those with disabilities.

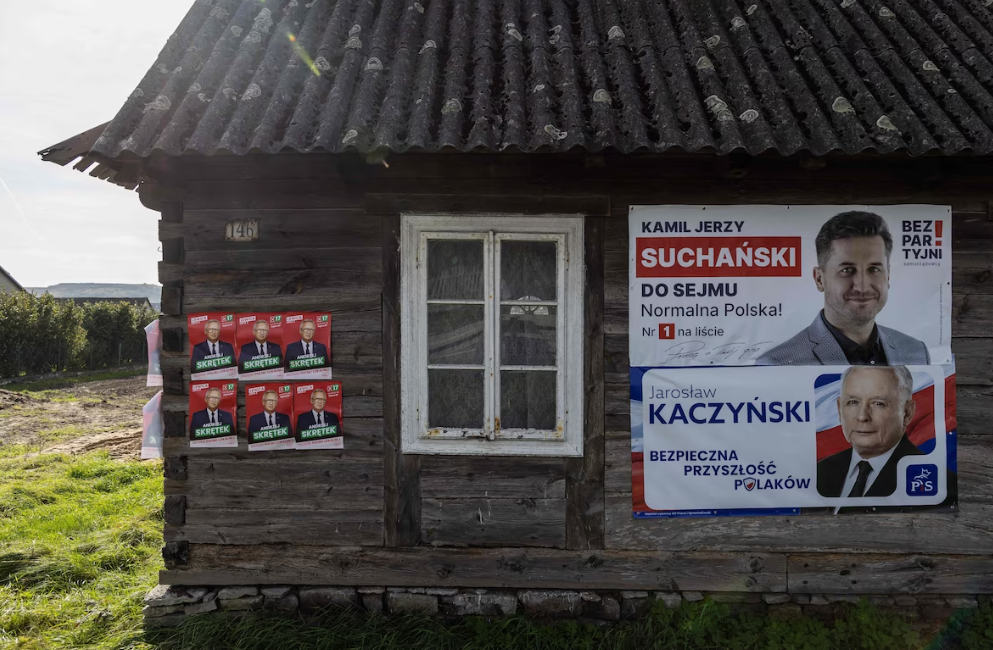

The ruling party insists the changes are about improving accessibility. The opposition argues that the measures will only boost turnout among the elderly and voters in rural areas — two demographics that are part of Law and Justice’s core electorate.

One group that more reliably supports the opposition is expats. More than half a million Poles living abroad have registered to vote in this election — the highest in the country’s history. But there’s a new requirement that foreign voting districts submit their counts within 24 hours of polls closing. Poland’s commissioner for human rights, Marcin Wiacek, has warned that could disenfranchise voters.

Meanwhile, though mandated by law, the government declined to reapportion constituencies in line with population shifts. That means people in sparsely populated rural areas have more voting power. One group advocating that city dwellers vote in other districts calculated that candidates in Warsaw have to win 98,000 votes while candidates in the agrarian east need to win only 74,000 votes.

And if the election results are challenged? That could highlight a further weakening of Poland’s institutions: The government has limited the independence of the National Electoral Commission and the Supreme Court.